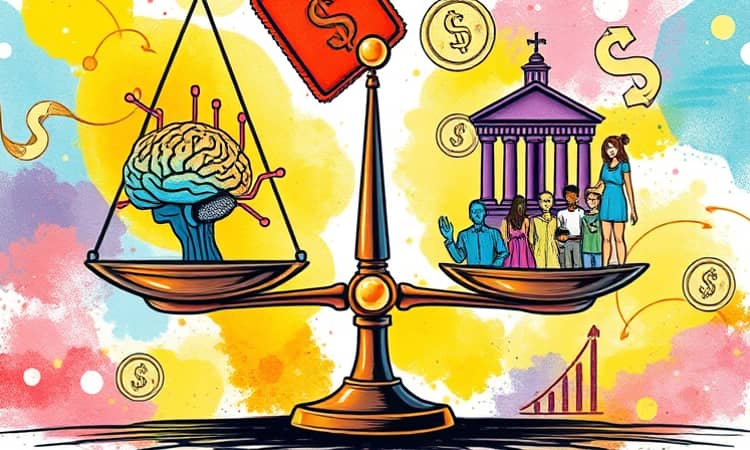

Artificial intelligence is transforming financial services at an unprecedented pace. From loan approvals to investment advice, AI systems now underpin critical decisions that shape individual lives and global markets. As institutions embrace automation, the question of ethics becomes pivotal: how do we harness the power of algorithms without compromising justice, trust, and stability?

In this article, we explore what “ethics of AI in finance” truly means, examine real-world use cases and documented harms, and outline practical solutions to embed fairness, transparency, and accountability into every model.

Defining AI in Finance and Why Ethics Matter

AI in finance encompasses a broad array of technologies—machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing—applied to credit scoring, fraud detection, algorithmic trading, robo-advisory, underwriting, insurance pricing, KYC/AML compliance, collections, and customer analytics.

Ethics of AI in finance focuses on ensuring fairness, transparency, accountability and preventing discriminatory outcomes that can deny credit, inflate insurance premiums, or flag innocent customers as fraud risks.

Why is this so important? Today’s AI systems learn from historical financial data reflecting inequalities. Without deliberate safeguards, they risk automating and amplifying past injustices, undermining trust and exacerbating social disparities.

Key Ethical Themes: Fairness, Bias, and Transparency

Three interlinked themes define the landscape of ethical financial AI: fairness, bias, and transparency. Understanding their origins and impacts is the first step toward meaningful remediation.

Fairness & Bias in AI

- Historical and structural bias: Legacy discrimination, such as redlining, is encoded into credit histories and property valuations.

- Unrepresentative data: Women, minorities, gig workers, and immigrants often appear in smaller samples, leading to skewed predictions.

- Proxy discrimination: Variables like ZIP code or transaction patterns can stand in for protected attributes, perpetuating unfair treatment.

- Optimization trade-offs: Prioritizing accuracy or profit can conflict with group and individual fairness goals.

Documented evidence is stark. A 2024 Urban Institute study of Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data showed Black and Brown applicants were more than twice as likely to be denied mortgages compared to white applicants, despite similar financial profiles. MIT–IBM research revealed “racial premiums” of 5.3 basis points on purchase mortgages for African American borrowers versus white borrowers, even when group fairness metrics were satisfied.

The 2019 Apple Card controversy highlighted gender bias: public figures reported credit limits up to 20 times higher for men than for women with comparable credit scores. While regulators found no legal violation, the episode underscored the opacity and potential for perceived discrimination in AI models.

Transparency & the Black Box Problem

Complex models—deep neural networks and ensemble methods—often operate as inscrutable “black boxes.” Customers and regulators demand clear explanations for adverse decisions: Why was a loan denied? Which factors influenced an insurance premium? Without transparency, institutions cannot detect and correct model bias or demonstrate compliance with fair lending laws.

Explainable AI (XAI) practices are emerging to bridge this gap:

- Local explanations: Tools that articulate why a specific applicant was denied credit.

- Feature importance analysis: Techniques to identify and mitigate proxy variables.

- Global interpretability: Simplifying complex models into human-friendly rules for auditing.

Real-World Evidence and Ethical Risks

The stakes of biased AI extend beyond individual harm. Consumer exclusion, inflated borrowing costs, and wrongful fraud flags erode public trust and invite legal penalties. The EEOC’s 2023 settlement with iTutorGroup over age discrimination in hiring demonstrates that algorithmic bias can trigger regulatory enforcement, even outside finance.

Systemic risks also arise when multiple firms deploy similar AI strategies. Herding behavior and feedback loops can amplify market volatility, while the concentration of power in a few data providers creates new single points of failure. An “ethics of complexity” must address not only fairness at the individual level but also structural vulnerabilities across the financial ecosystem.

Regulatory and Policy Context

Governments and standard-setters worldwide are tightening oversight of AI in finance. Key legal frameworks include the Fair Housing Act, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, and evolving guidelines for model risk management that explicitly cover AI and ML models.

Regulators now expect firms to maintain detailed documentation and continuous monitoring of model design, validation, and performance to detect disparities. Supervisors review AI lifecycle governance, demanding evidence that institutions considered ethical risks at every stage.

International cooperation is growing, with bodies like the G7 and IOSCO exploring coordinated standards to mitigate cross-border risks and ensure consistent protections for consumers.

Practical Governance and Technical Solutions

Bridging the gap between ethical ideals and operational reality requires both governance frameworks and technical tooling. Financial institutions should adopt multi-layered strategies that integrate policy, process, and technology.

- Governance frameworks: Establish an AI ethics committee with diverse representation, clear charters, and escalation pathways for ethical concerns.

- Pre-processing techniques: Employ data rebalancing and synthetic sampling to correct for historical under-representation.

- In-processing adjustments: Use fairness-aware machine learning algorithms that optimize for equity metrics alongside accuracy.

- Post-processing remedies: Calibrate model outputs to align with fairness thresholds without sacrificing overall performance.

Explainability tools should be embedded into the model development lifecycle. Automated dashboards can highlight shifts in performance across demographic groups, while regular audits with external experts help validate fairness and transparency claims.

Finally, structured governance frameworks and policies must dictate how AI is tested, deployed, monitored, and updated. Continuous training for data scientists, ethicists, and business leaders fosters a culture of shared responsibility.

By integrating ethical considerations at every step—from data curation to post-deployment monitoring—financial institutions can build AI systems that not only drive innovation and efficiency but also uphold the values of fairness, accountability, and trust. In doing so, the industry can ensure that the immense promise of AI serves all members of society, rather than reinforcing existing divides.